Permaculture is growing. Education and research are expanding. Interesting demo sites are becoming available to visitors. Permaculture ‘dots on the map’ are multiplying.1 All this is good news. What was a lifestyle choice for a few, based on a set of ethics, principles and techniques, is starting to look like a movement. Some people may be drawn to permaculture as a political movement.2 Others would prefer an anti-political understanding of permaculture,3 which still offers the prospect of widespread world change. The Bengali poet and polymath, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) offers such a model.

Tagore

often insisted he was not a philosopher or a scholar. He was not

interested in theories or utopian visions. His authority comes from

his practical efforts over fifty years to revive traditional Indian

society, which had been severely disrupted by British rule. His

remedy for a broken society was to heal it from within. Cooperation

was the key. People must get together in their local communities to

help each other and themselves. To give them a start, they would need

advice and expertise, suitable training and education, health and

welfare provision, affordable finance, and encouragement towards

developing participative government and local conflict resolution.

Most importantly for Tagore, to counter fatalism and apathy their

spirits must be raised, by reviving traditional arts and crafts,

music and story-telling, fairs and festivities. Tagore’s motivation

changed over the course of his rural reconstruction efforts:

initially he felt sympathy and a sense of responsibility as a

landlord, next he tried to set out a national programme of

constructive self government, lastly he pinned his hopes on bringing

about change through education.

Tagore was both an indefatigable man of

action and a compulsive writer who left a vast written legacy.4

Fortunately for us, his ideas on world change can be appreciated by

studying just five pieces of writing: two poems: ‘Call Me Back to

Work’ (1894) and ‘They Work’ (1941) and three essays: ‘Society

and State’ (1904); ‘Nationalism in the West’ (1917) and ‘City

and Village’ (1928) (all available at www.tagoreanworld.co.uk).The

dates of the two poems span the period over which Tagore was working

to revive Indian village society. ‘Call Me Back to Work’ shows

vividly the Poet’s compassion and commitment. In the final stanza

he urges himself into action:

Gather

yourself, O Poet and arise.

If you have courage bring it as

your gift.

There is so much sorrow and

pain,

a world of suffering lies

ahead,—

poor, empty, small, confined and

dark.

We need food and life, light and

air,

strength and health and spirit

bright with joy

and wide bold hearts.

Into the misery of this world, O

Poet,

bring once more from heaven the

light of faith.

It was a revelation for Tagore when he

was put in charge of the family estates in East Bengal (now

Bangladesh) in 1891. He was deeply moved by the natural beauty of the

region and the simple life of the common people. He saw the deep

despair which pervades rural life all over the country and determined

to improve the conditions with programmes of rural development. The

root cause of this despair was British imperialism. The British

introduced private land ownership and created an urban middle of

professionals and administrators. The absentee urban landowners

exploited and neglected their tenants.

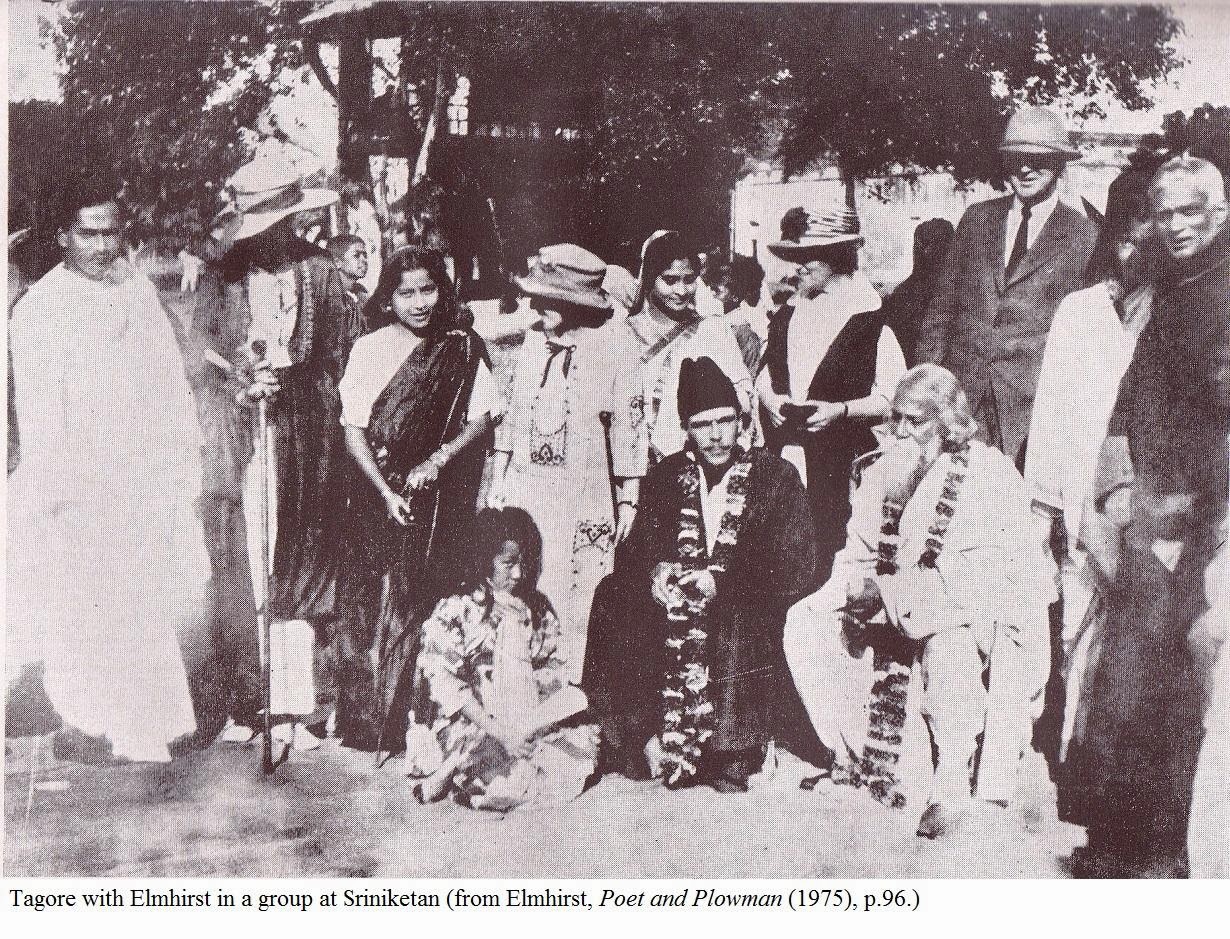

Tagore moved his base to Santiniketan

in West Bengal in 1901, and continued rural reconstruction work in

the neighbouring villages, as well as maintaining his interest and

involvement in the Tagore estates. In 1903 the British government in

India announced their intention to partition Bengal, into a largely

Muslim East and a largely Hindu West. Popular objection to this

‘divide and rule’ measure manifested as protest marches and a

‘Swadeshi’ boycott of British good, particularly cloth. Tagore

became a leader of the protests, wrote patriotic songs, gave stirring

speeches and led a demonstration of Hindu-Muslim solidarity involving

tying friendship bracelets. He favoured transforming the Swadeshi

boycott into a move towards ‘Constructive Swadeshi’, and he urged

urban landlords to return to their estates and engage in reviving

village craft industries and local fairs. His essay ‘Society and

State’ (Swadeshi Samaj in Bengali) was originally a public

address he gave in 1904, at a meeting to discuss the failure of the

British government in Bengal to solve a problem of water shortage. In

the essay Tagore makes a powerful case for devolving decision making

and responsibility to grassroots level, thus reviving traditional

Indian society: Tagore explains that their country has traditionally

had a society, but not a state in the English sense:

What in English concepts is

known as the State was called in our country Sarkar or

Government. This Government existed in ancient India in the form of

kingly power, but there is a difference between the present English

State and our ancient kingly power. England relegates to State care

all the welfare services in the country; India did that only to a

very limited extent.

Tagore goes on to explain that in

India, ‘social duties were specifically assigned to the members of

society’, and the king made his contribution, like any other

wealthy member of society, and the word for social duties is dharma,

which ‘permeated the whole social fabric’.

Tagore

was unable to persuade the English-educated urban intelligentsia to

adopt his political programme, and the negative boycott turned

violent and destructive, and so he turned his back on the protests

and returned to his base at Santiniketan, where he implemented the

Constructive Swadeshi ideals on a small scale. He had started a small

school at Santiniketan in 1901 where the teaching encouraged

creativity, engagement with nature, local food growing, and learning

about life in the villages. The school grew in numbers and led

eventually to Tagore establishing an international university named

Visva-Bharati. A key element of the university was its Institute of

Rural Reconstruction named Sriniketan. Tagore described the

philosophy behind this venture in his essay ‘City and Village’,

in which his aims appear very modest. He explains that rather than

think of the whole country, it is best to start in a small way: ‘If

we could free even one village from the shackles of helplessness and

ignorance, an ideal for the whole of India would be established’.

Obviously Tagore failed in his efforts.

Vandana Shiva, the indefatigable campaigner for Indian farmers’

rights against agribusiness monopolies, tells of the poverty and

despair, with more than 270,000 farmers caught in the debt trap

committing suicide since 1995.5

Curiously enough, Tagore’s failure then gives us hope a century

later. He foresaw, if not the circumstances Shiva describes, but the

dehumanising effect of industrialism and the nation state, and he

wrote a penetrating critique in ‘Nationalism in the West’, which

is the text of a lecture he gave over twenty times in 1916 in the

United States.

The final piece of Tagore’s writing,

the poem ‘They Work’, written in 1941 shortly before he died,

provides a particularly important and optimistic insight. Its subject

is the transience of the empires which had successively ruled India:

the Pathans, the Moghuls, then the ‘mighty British’:

Again, under that sky, have come

marching columns of the mighty British, along iron-bound roads and in

chariots spouting fire, scattering the flames of their force.

I know that the flow of time

will sweep away their empire’s enveloping nets, and the armies,

bearers of its burden, will leave not a trace in the path of the

stars.

Through

all these changes, the people who carry out the work go on: ‘Empires

by the hundred collapse and on their ruins the people work.’

Translated into permaculture terms, and the situation we are faced

with today, what Tagore is saying is that all parasitic empires,

including modern industrial civilisation, the nation state and

finance institutions, will inevitably exhaust the resources which

sustain them, and so decline and fall. Then the people who work will

reclaim and revive the degraded land, and life will go on.

The message for the permaculture

movement is that we need not think of saving or changing the world

but of returning to normal, and rediscovering the convivial delights

of being human.

2

See ‘Permaculture and Politics’

(http://permacultureambassadors.blogspot.co.uk/2014/02/permaculture-and-politics.html

)

3

‘Anti-political’ can mean not ‘Party political’, whether

Green or Leftist; also not reliant on influencing political leaders

at national or international levels; also not understood in

revolutionary terms, whether Marxist or Anarchist. Some of us, of

course, take the view that everything in human life is political.

4

An indication of Tagore’s genius is given by the tribute to mark

Tagore’s 80th birthday by Ramananda Chatterjee,

‘Rabindranath Tagore’ at www.tagoreanworld.co.uk

.

5

Vandana Shiva, ‘How economic growth has become anti-life’, The

Guardian, 1 November 2013,

(http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/01/how-economic-growth-has-become-anti-life

[20/2/14])

No comments:

Post a Comment